Story and photos by Ellen Murphy

The musty smell of dust and age assault the senses as Giuseppe Aguzzi welcomes visitors at the door to the Bishop’s archives. The archives detail life in Cagli, Italy.

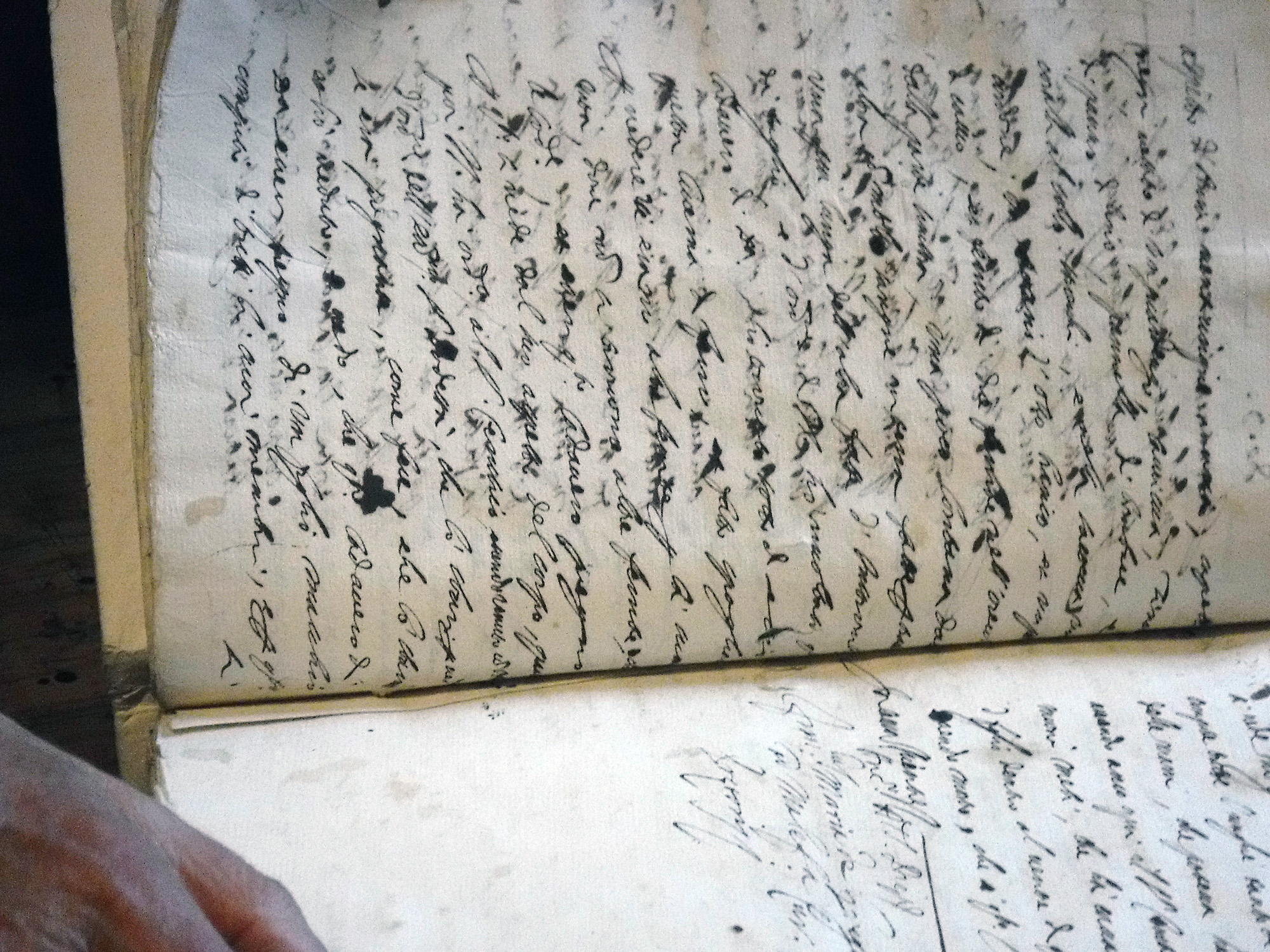

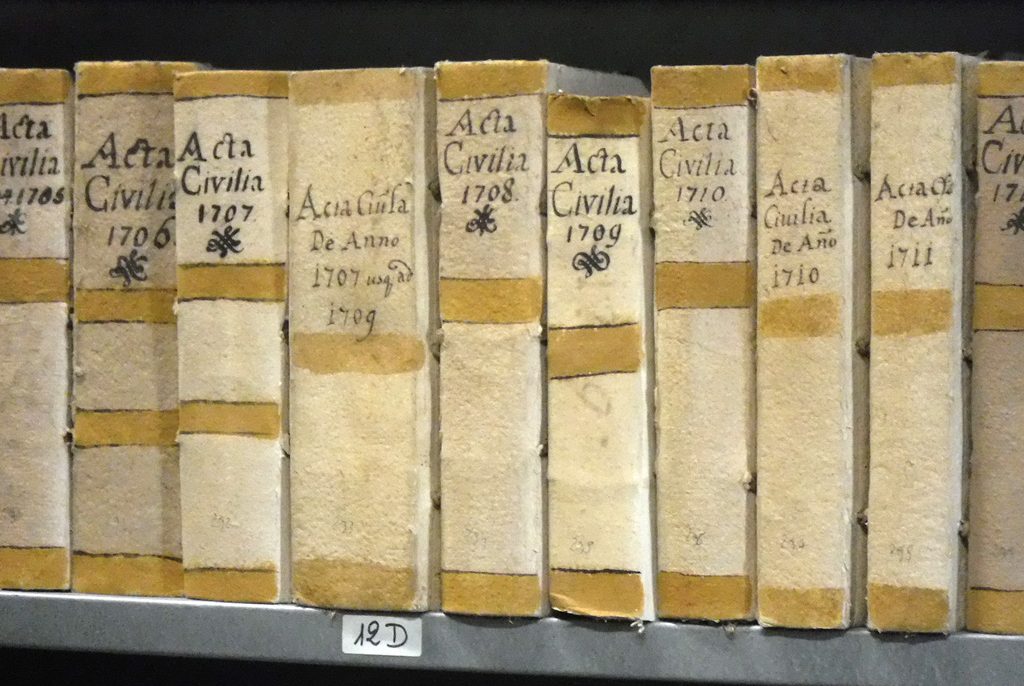

The parchments are yellowed with age. The script is elaborate cursive completed by hand with goose quills. Many of the papers reflect everyday life of the parishioners in 800 AD—business licenses, judicial sentencings, purchases, and sales of everyday items; births, deaths, and marriages. They detail the labor of stonecutters, woodworkers, and artisans hired for various work within the walls.

For most of his life, Giuseppe has been the caretaker for San Francesco, a medieval church in Cagli. Recently, Giuseppe has been asked to work with the archives by the Bishop. He has the daunting task of putting them in order for future generations so that they understand the significance of the town in the digital age.

This priceless history must be preserved before it is lost forever, Giuseppe says. Over time, the ink will fade, and the paper will become brittle and turn to dust. Giuseppe’s labor of love becomes evident in his preservation efforts. He is Cagli’s keeper of time.

Giuseppe shares the stories of San Francesco church, beginning with the tale of a local legend, St. Francis, who traveled through Cagli and left behind several trusted followers. The followers settled and preached the Gospel in Cagli.

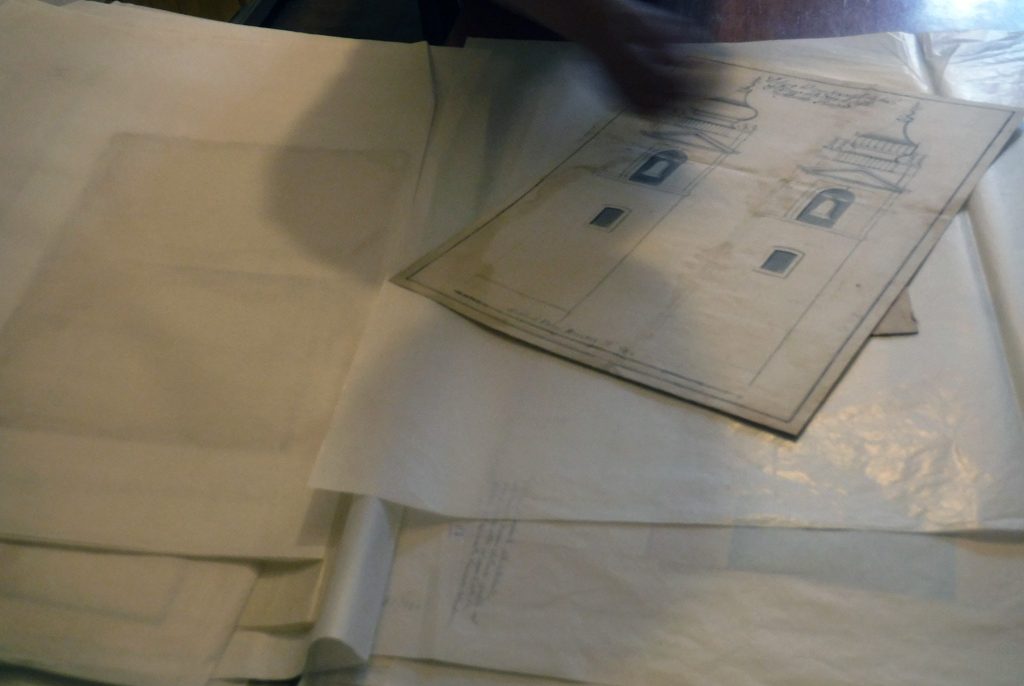

As he moves through the church, Giuseppe explains the significance of the art and design. The church, he says, is typical of the Roman/Gothic style of the time. Blueprints from the archives hold proposals that were rejected and accepted during construction.

Construction of the church began six years after the death of St. Francis and was completed 50 years later. The consecration of San Francesco took place in 1250.

During the plague from 1629 to 1631, the artwork was diluted, Giuseppe says. The walls and ceilings were whitewashed and disinfected, creating blank spaces in the frescoes that resemble forever-lost puzzle pieces.

The church has seven altars. The first altar to the left of the sanctuary displays a hand-carved crucifix made from one piece of wood in the 1400s. A life-size Christ on the cross, made about 1500, is attached, giving the illusion the work is all one piece.

In 1622, the famous Cagli stonecutter Elpidio Finale created intricate carvings on the altar surrounding the crucifixion, Giuseppe says. The hand carvings credited by a simple plaque on the side that reads, “Finale 1622. Elpidio DCagli.” (Completed 1622 by Elpidio of Cagli.)

The carvings tell the story of St. Francis, beginning with his departure from the army and including key points in his life as a monk as well as several of his miracles. The ornaments across the front of the altar display key Franciscan Saints: Claire, Elizabeth, Anthony, and Bernard.

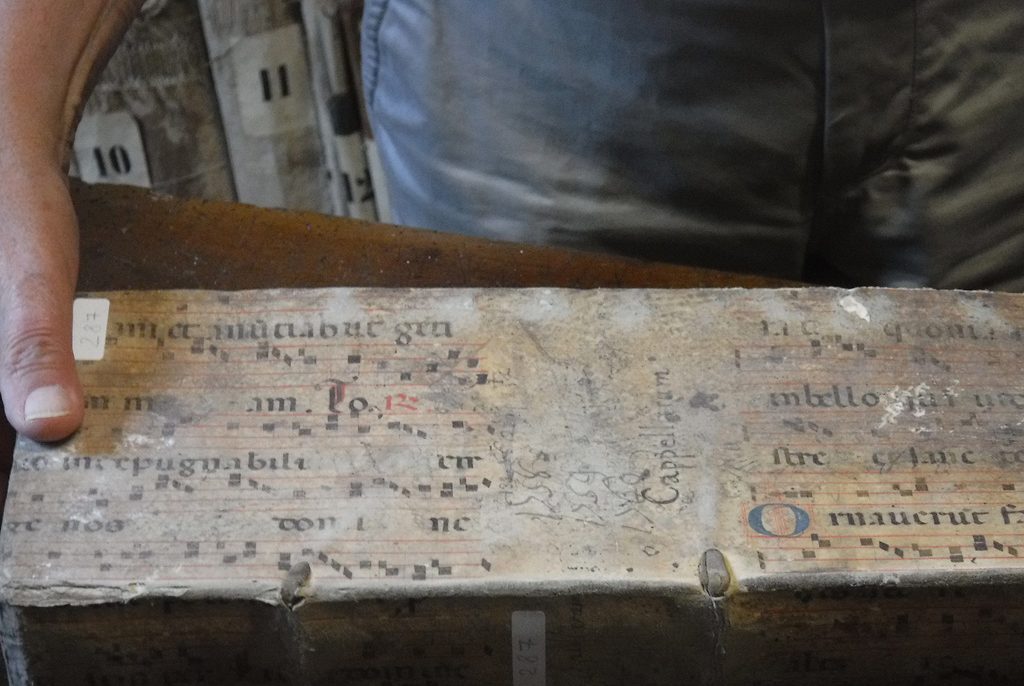

An organ was added to the church in the 1500s. The instruments’ tones were made to fit the Renaissance music of the time. To keep the instrument in tune, the organ is played only occasionally such as special holidays, festivals, and events. The organ is incapable of playing anything “modern,” Giuseppe says.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, San Francesco benefited from the prospering Cagliesi. Cagli became a thriving city whose residents specialized in art, music, and tanning. The wealth led to ornate additions to San Francesco, including the hiring of Lapis, the renowned Renaissance painter. Lapis was a native of Cagli.

The Cagliesi specialized in using archery and became famous for making crossbows, arrows, and bows, Giuseppe says. Residents became renowned as mercenaries. When they returned to Cagli, they brought wealth with them.

As he takes his visitors on a journey through time, Giuseppe proudly displays a scroll from Pope Leo the Fourth, circa 847- 845 AD. The Papal seal is attached. Giuseppe explains that the “bolo” cylinder discs prove that the Pope sent the missive for the Parish of Cagli. As the keeper of the archives, Giuseppe says, he is proud of his work.

Comments